Which production assets for more resilient and sustainable agricultural and food sectors? Which investment needs? Which stranded assets?

Report only available in French

Investment choices in the agricultural and food sectors in the coming years will be decisive

To ensure the long-term viability of their production and to cope with crises, the French agricultural and food sectors must evolve towards more resilient and sustainable systems. More resilient in order to reduce their vulnerability to increasing climatic and geopolitical shocks. More sustainable in order to reduce pressures on key agricultural production factors (climate, water, soil and biodiversity).

However, implementing this transition is extremely complex. It involves coordinating climate, health and environmental challenges with economic, social and geopolitical considerations, while aligning the specific characteristics of a wide range of sub-sectors (cereals, pulses, dairy cattle, pigs, etc.) and the diverse actors involved in them.

Anticipating investment is essential in order to implement this transition while limiting its cost. Fixed assets in the agricultural and food sectors have lifespans ranging from 5 to 80 years. Investing today in production facilities that prove unsuitable within 10 or 30 years would create or reinforce lock-ins, increase future investment requirements, or generate capital losses.

The challenge is even more crucial as several waves of investment are currently underway or forthcoming in these sectors. On farms, the upcoming wave of new entrants is very likely to be accompanied by a wave of investment. Downstream, several investment plans are underway or forthcoming to modernise facilities, particularly grain storage, slaughtering, and milk processing installations.

An existing stock of approximately €115 billion in agricultural and food production assets in France

We estimate that in 2023 the value of production assets (buildings, equipment and plantations) dedicated to agricultural and food production in France amounted to approximately €115 billion. Nearly half of this stock is dedicated to agricultural production: tractors, milking parlours, livestock buildings, vineyard plantings, etc. An equivalent amount is dedicated to downstream activities, 70% of which relates to the “immediate downstream” segment (collection, sorting, storage, slaughtering/cutting, primary processing), whose infrastructure is inseparable from agricultural production. Finally, 4% is dedicated to upstream activities: fertiliser production, plant protection products, compound animal feed, and agricultural machinery and equipment.

Investment, amounting to approximately €25 billion in 2023, is particularly correlated with the economic cycle and primarily aims at efficiency gains. Investment on farms increased by 40% (excluding inflation) between 2017 and 2023, in connection with favourable economic conditions. These investments were mainly made in the largest farms and those specialising in dairy cattle, pigs and poultry. They have enabled gains in labour productivity. Downstream, companies are increasingly consolidating and are also investing to enhance competitiveness. Both on farms and in downstream firms, investment capacity is uneven.

The transition affects production assets across all stages and value chains, calling for coordinated and planned investment

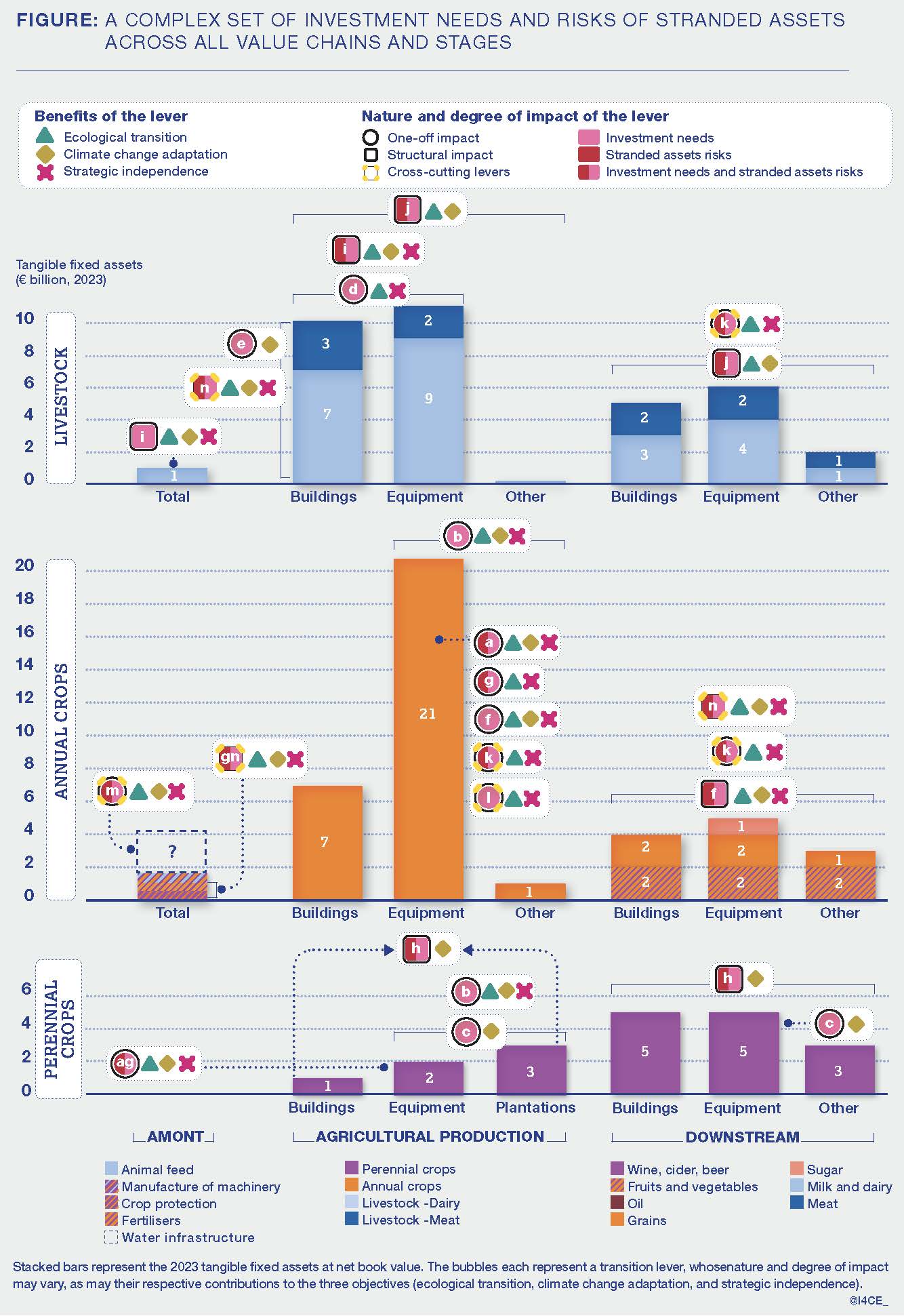

Out of the total, €100 billion of production assets across all stages and value chains are potentially affected by the transition — not only to meet environmental objectives, but also to adapt to climate change and to improve France’s independence in strategic products such as fertilisers, plant proteins (e.g. soy), and fossil fuels.

Additional investment will be required, and a significant share of capital losses (stranded assets) could be avoided. However, the scale of these costs remains difficult to estimate — not only due to a lack of consolidated data, but also because the total amount depends on the type of transition pursued and the degree of planning and anticipation.

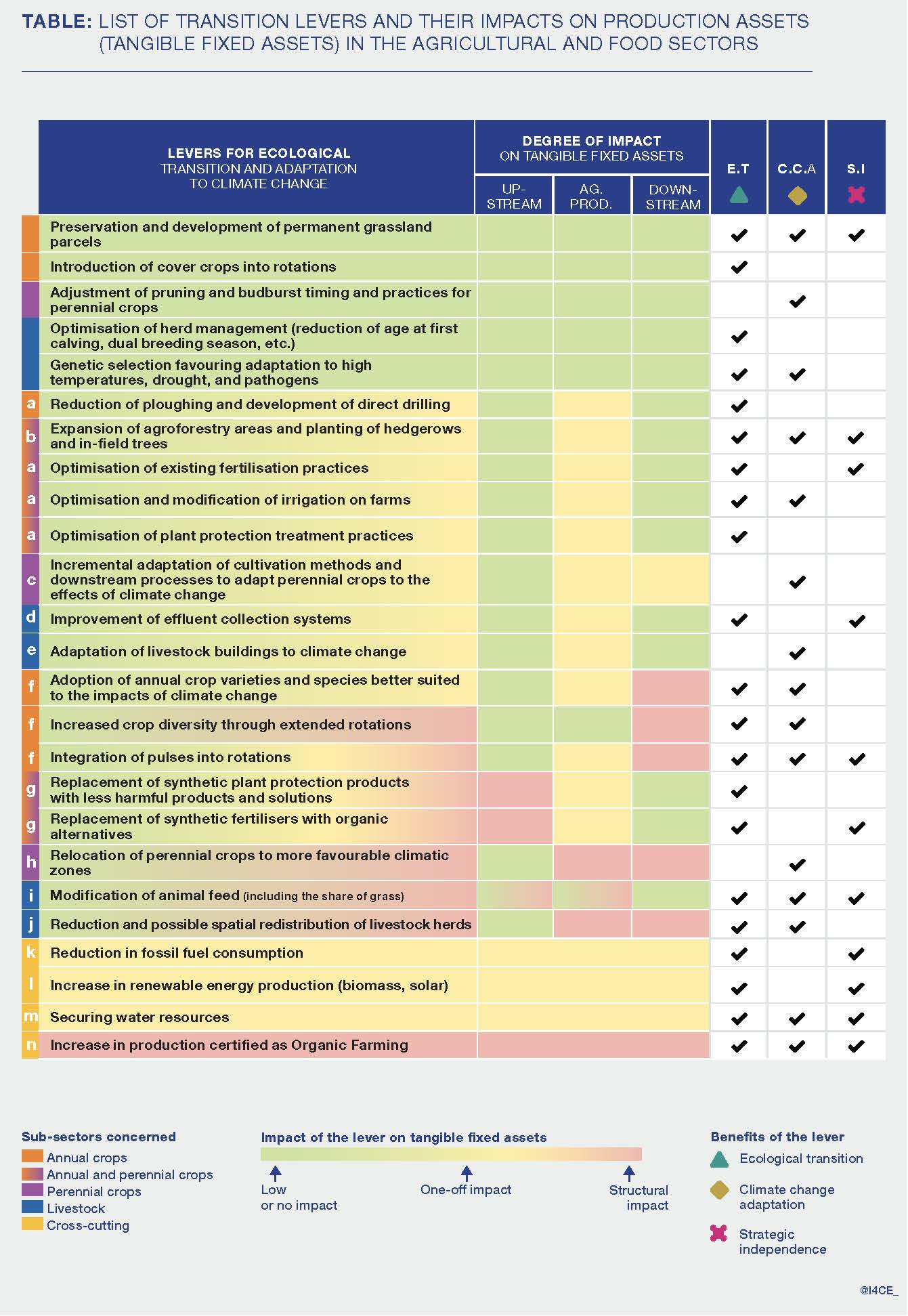

Coordination and planning of investments can help limit the cost of the transition. Indeed, the transition requires simultaneous changes across several value chains, stages and territories (Table). A single production asset may be affected by several transition levers: some requiring investment to optimise or improve it, others requiring replacement (Figure). Coordinated and planned investment choices could reduce the overall cost of the transition by anticipating needs and thus avoiding potential capital losses.

Public authorities have a role to play in orchestrating this transition: roadmaps guiding investment by sub-sectors and by regions are needed. A forthcoming part of this study, analysing the current orientation of public support for agricultural and food investment, will be published in the coming months.

One-off investment needs to be integrated into the standard equipment renewal cycle

The transition implies one-off investment needs, particularly in agricultural production assets. The total value of the production assets concerned currently amounts to approximately €80 billion. These include:

- Replacing the propulsion systems of agricultural machinery and the energy sources of downstream facilities.

- Replacing or modifying specific equipment to improve and/or optimise fertilisation practices, soil management, irrigation, plant protection treatments, and livestock effluent management.

- Acquiring new tools for the development of hedgerows and agroforestry (planting and maintenance equipment), for adapting livestock buildings and perennial crop activities (viticulture and arboriculture) to climate change, for energy production, and for securing water supply.

A large share of these needs can be integrated into the standard equipment renewal cycle. This is the case for machinery, much of which will in any event be replaced by 2050 due to its relatively short lifespan. Transition objectives can therefore be incorporated into renewal decisions, albeit potentially at additional cost.

Infrastructure reconfiguration needs to be coordinated across value chains and territories

The transition also entails more structural investment needs, affecting the configuration of buildings and perennial plantations and potentially generating stranded assets. The agricultural and food production assets affected by these more structural needs amount to approximately €70 billion. These include:

- Reconfiguring grain storage buildings and facilities to adapt to the necessary diversification of crop production, including the development of pulses.

- Reducing production capacity and possibly relocating part of livestock activities, both on farms and downstream.

- Relocating part of perennial crops (vineyards and orchards) to more favourable climatic zones where incremental adaptation to climate change reaches its limits.

- Reconfiguring input production facilities, certain livestock buildings, and downstream collection and processing tools to meet organic farming specifications.

Here again, part of the reconfigurations and relocations can be integrated into the standard renewal cycle, provided they are anticipated and coordinated. For example, in response to ageing facilities, grain collection operators are considering a major investment plan to renew silos whose lifespan can reach 80 years. The needs arising from crop diversification and the development of pulse value chains can be incorporated into this plan — not only to meet environmental objectives, but also to adapt to climate change and strengthen France’s strategic independence.