Relaxing EU standards on CO2 emissions won’t save the EU’s automotive industry, or help consumers

Recently, car manufacturers have been calling for a relaxation of CO2 emission standards for cars and vans and the 2035 phase-out target for new internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, by including some flexibilities. They point in particular to the crisis the industry has faced in recent years, growing competitive pressure from China, and insufficient demand for electric vehicles (EVs) in Europe, as reasons for the sector needing more time for the transition required to meet the targets. As the European Commission (EC) prepares to publish its package for the automotive industry, including a revision of CO₂ standards for cars and vans, this blogpost examines the realities behind the difficulties currently faced by car manufacturers and the consequences of relaxing and postponing the planned EU regulations for this sector.

A closer look shows that the sector is not facing the degree of difficulty that it claims, and that the decline in sales volumes stems mainly from the manufacturers’ chosen strategy to focus on selling larger models, particularly SUVs. This is why, despite lower sales volumes, their operating margins have increased in recent years. This premiumisation trend is not new, but it has accelerated in recent years, to the point of backfiring, with manufacturers now facing a sharp drop in sales and factories standing idle. At a time when the EU is falling behind its climate targets for the transport sector, delaying or relaxing EU regulations will not save Europe’s automotive industry, and might even jeopardise many of the investments already made in the electrification of the whole sector’s value chain.

Furthermore, introducing flexibility for other vehicle types, such as plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) or e-fuels, in the regulations offers no economic or environmental benefit to consumers, while costing them significantly more over the vehicle’s lifetime, compared to battery electric vehicles (BEVs). Finally, altering the sector’s decarbonisation trajectory would also send extremely negative signals to anyone seeking to invest in the decarbonisation of the automobile sector, creating significant uncertainty about the EU’s determination to maintain a clear course on its decarbonisation targets.

The future of the European automotive sector will be electric. If the EU car industry continues to prioritise highly profitable ICE models for as long as possible, it risks being overtaken by international competitors, particularly China. Once this happens, catching up may prove extremely difficult, potentially putting the future of Europe’s automotive industry at risk for good.

Falling car sales in Europe are linked to structural market factors, not to EU regulation

The crisis affecting the automotive industry in Europe is primarily due to a reduced demand, especially for ICE vehicles

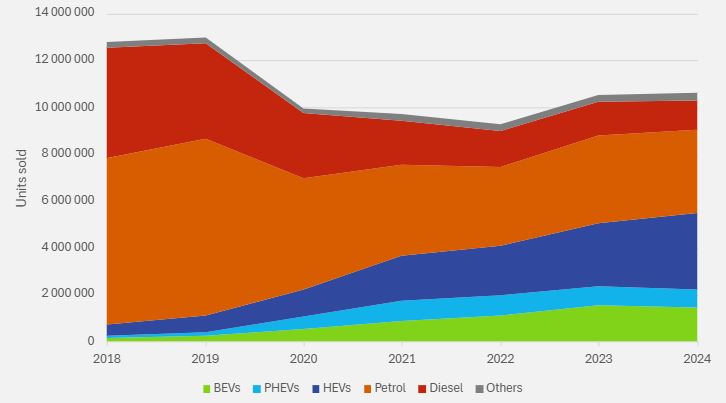

Since the start of the pandemic, the automobile sector has seen its sales volumes decline significantly across Europe. After a drop of more than 23% in 2020, passenger car sales have not returned to their pre-Covid levels, stabilising at around 80% of 2019 sales despite the slight recovery observed over the past two years. These declines differ across vehicle types. The sales of BEVs and hybrid vehicles (plug-in and non-plug-in) have increased significantly, rising by around 49% and 37% per year respectively since 2018. Meanwhile, diesel and petrol cars have been in decline over the same period, with sales decreasing by around 11% and 20% per year, respectively (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: New passenger car registration in the EU per fuel type

Source: I4CE from ACEA, 2025.

Taking a longer-term perspective, the European automotive sector has been describing itself as being in a state of crisis for quite some time. As early as the start of the 2000s, French and Italian manufacturers, which mainly specialised in small and compact vehicles, were quickly overtaken by the “premiumisation” of the car market. The lowering of trade barriers at the time increased competitive pressure on these manufacturers, whose market segments offered lower margins and where market segments were more price-elastic. At the same time, consumer preferences across Europe have increasingly gravitated towards larger vehicles. Consequently, the share of the production in France of Renault and Stellantis, relative to their total production in the EU and neighbouring countries, fell sharply, from 64% in 2003 to just 25% in 2020 (Hertie School Jacques Delors Centre, 2025). During the same period, the premium group (Mercedes, BMW, Audi and Volvo) saw its market share increase from 13% to 21% (Pardi, 2025). To remain competitive while continuing to produce low-cost small vehicles, these manufacturers chose to relocate their production. In 2023, French car manufacturers produced only 23% of their light vehicles in France, compared with 53% in 2005. Most production is now located in Spain, Morocco, Romania, and Slovakia (Pardi, 2025).

The difficulties faced by German manufacturers are more recent. Over the same period, German car manufacturers succeeded to combine lower-cost manufacturing in Central and Eastern Europe countries with high-value flagship plants in Germany, focusing on R&D and premium-segment production (Hertie School Jacques Delors Centre, 2025). But very recently, German manufacturers have started to face difficulties as well, mainly due to their declining sales outside Europe, particularly in China. Volkswagen, in particular, has lost its market-leading position in China, with its share of the passenger vehicle market dropping from 19% in 2019 to 14.5% in 2023 (Hertie School Jacques Delors Centre, 2025). This shift in the Chinese market towards its domestic manufacturers has led to factory closures and layoff plans by German car manufacturers, making the issue particularly politically sensitive in Germany.

Fewer cars sold but with higher profits for car manufacturers

The decline in new-car sales in recent years is largely attributable to rising prices. According to the Institute Mobilité en Transition (IMT), between 2020 and 2024, the list prices of new vehicles purchased in France rose by €6,800 including VAT, or +24%. A similar increase has been observed in other Member States. While some of the price increase is imposed on manufacturers due to rising inflation and an energy-mix effect (mainly with more hybrids and BEVs in the sales mix), another significant part is the result of deliberate choices, as manufacturers have shifted towards premium models, with higher unit margins (IMT, 2025).

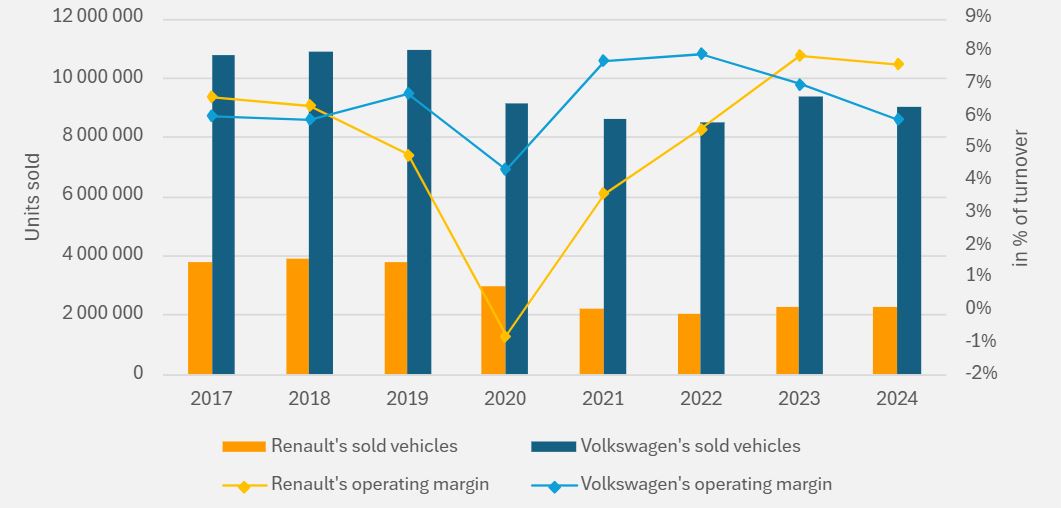

This is why, although new-car sales have declined in recent years, manufacturers’ margins have at best remained stable and even increased in most cases. For example, Renault Group’s operating margin reached 7.6% in 2024 compared with 4.8% in 2019, even though its annual global registrations fell by 40% between 2019 and 2024. Volkswagen’s operating margin rose as high as 7.9% in 2022, compared to 6.7% in 2019, even though its vehicle sales volumes declined by 23% over the same period.

Figure 2: Renault’s and Volkswagen’s global sales volumes and operating margins

Source: I4CE, from Renault’s financial results from 2017 to 2024, Volkswagen’s financial results from 2017 to 2024.

This largely voluntary strategy of reducing volumes has significant social impacts on employment, as illustrated by Volkswagen’s recent announcement to cut over 35,000 jobs in Germany by 2030. Between 2019 and 2024, employment in the automotive sector fell by 25% in France, by 9% in Italy and by 7% in Germany. The premiumisation of vehicles also has broader consequences for the affordability of cars for households, as cars increasingly risk becoming akin to luxury goods. Most households rely on the secondary market, which is directly shaped by choices made in the primary market, and are therefore affected by this “premiumisation” strategy.

Staying the course on the 2035 target to preserve the EU automotive industry and consumer purchasing power

Keeping combustion and hybrid models will cost consumers over time

With the 2035 phase-out rules for new ICE vehicles, car manufacturers are seeking to introduce certain flexibilities for PHEVs and e-fuels vehicles. However, not only are these models less environmentally beneficial than manufacturers claim, they also present cost disadvantages. Several studies show that the total cost of ownership (TCO)(1) of BEVs is already more competitive than those of ICE vehicles and alternatives such as PHEVs or e-fuels vehicles.

A study by Agora Verkehrswende on the German vehicle fleet shows that the TCO of BEVs is as at least as competitive as that of ICE cars (if not more so), both with and without subsidies, for vehicle classes ranging from mid-size to large and luxury. Another study by ERM for BEUC shows that the TCO of BEVs for new cars will become the most competitive from 2026 for mid-size cars, 2027 for small cars, and 2029 for large cars. The study also shows that, by 2035, the TCO of e-fuels vehicles will be 20% higher than that of BEVs.

Figure 3: Four-year TCO for first-hand owners of medium cars against year purchased for a range of engine types

Source: ERM, Cost of zero-emission cars in Europe, 2024.

Regarding the used-car market (second- and third-hand buyers), BEVs are already competitive and are expected to remain so at least until 2040. While second-hand EVs usually currently benefit from a significant purchase discount, this discounting is expected to lessen in the coming years as the EV market expands. Nevertheless, EVs’ TCOs will remain significantly lower than those of other engine types.

This last point is crucial from the perspective of households’ affordability of car ownership. Today, the majority of middle- and lower-income households in the EU purchase their vehicles from the second-hand market. The used-car market is largely shaped by the choices made in the new-car market. Unless the new car market shifts to electric, middle- and lower-income households will less be able to purchase EVs, despite their lower operating costs compared with their fossil-fuel counterparts.

However, for low-income households, EVs can still be unaffordable upfront due to the currently higher cost of batteries compared with combustion engines. Public authorities should carefully target subsidies towards lower-income households, enabling them to purchase an EV that will ultimately be less expensive for them over time. The Commission’s “small and affordable electric cars” initiative could instead provide a major opportunity to revive the EU automotive industry, while ensuring that all those in the EU have access to an affordable, decarbonised vehicle.

Delaying the EU’s 2035 target could undermine the whole EU automotive value chain

Postponing and relaxing EU regulations on the electrification of cars would limit the size of the EV market in the coming years, thereby undermining the profitability of the investments already made in the electrification of the automative sector.

First, many investments in the electrification of the sector have been made in the vehicle production sector itself. While Germany and France are already producing a large number of BEVs (1.2 million and 330,000 respectively), many investments in EV production are also planned in other European countries, particularly in Spain and Eastern Europe. However, some projects in the list risk being delayed or even cancelled due to the uncertainty around the future prospects for the market.

Second, rolling back or lowering the ambition of the 2035 target would also risk undermining the investments already made in European battery gigafactories. Battery manufacturing investment has shown strong momentum in recent years, reaching 12.5 billion euros in 2023, a 19.7% growth compared to 2022, although it declined by 20% in 2024 (I4CE, 2025). Many factories are currently under construction across Europe. If the announced projects and construction sites are completed, the total capacity that batteries could produce in the EU would be 753 GWh in 2030, exceeding the EU’s target of 550 GWh by 2030 (I4CE, 2025). However, despite this positive outlook, planned capacity might not materialise as anticipated, as external market shifts and technical disruptions could lead to delays or cancellations. According to T&E, over half of the gigafactory plants in Europe (whether existing, under construction or announced) remain at risk of delay or cancellation. If demand for EVs decreases in the coming years, the risks posed by these already completed investments could materialise and lead to factory closures – notably, a significant proportion of factories already in operation is producing fewer batteries than initially announced (I4CE, 2025).

Finally, substantial sums have also been invested in public EV charging points in recent years. This investment tripled between 2020 and 2023, reaching 2.6 billion euros in 2023 (I4CE, 2025). Slowdown in EV sales could also jeopardise these investments and severely hamper activity in this segment.

Staying the course on CO₂ standards is essential to safeguard the industries already committed to the transition. To also ensure their viability against foreign competitors, the EU could consider strengthening its local-content requirements for the whole EV supply chain. (T&E, 2025)

Boosting demand for EVs: the role of corporate fleets

Corporate fleets could play a major role in boosting EV demand in the next decade. The rise in vehicle prices has triggered the growing use of leasing options for both renting and purchasing cars, which has placed leasing companies at the forefront of new-vehicle acquisition strategies. The share of corporate registrations has been increasing, today representing six out of ten new-car registrations, up from five out of ten in 2015. Of these registrations, 50% come from leasing companies, while seven leasing companies have a 30% share of the total market, all of which belong to car manufacturers or large banks (T&E, 2024). This significant proportion across the EU underlines the key role that companies play in shaping national car markets by determining the new market stock entering the used-car market, since corporate cars are typically driven for only the first three years of a car’s lifetime. Thus, as long as these fleets are not electrified, a very large share of EU citizens will not be able to access to EVs, which would seriously jeopardise the achievement of EU’s emission reduction targets for this sector.

Despite their importance, corporates have a lower BEV uptake rate than private households (14.1% vs 15.6%) (T&E, 2024). One of the main factors behind this difference is the residual value of BEVs. As the business model of leasing companies is to own a car for a fixed period, the residual value of the vehicle plays an important role in determining its leasing cost. According to T&E, companies across major European markets charge consumers 57% more to lease a BEV than an equivalent petrol model. However, the T&E analysis also showed that the re-sale value assumed by leasing companies is generally lower than the actual average re-sale value of BEVs in the market. Factors cited to justify this often include the technological gap between older and newer BEV models and concerns about potential battery degradation. The Economic Analysis Council in France has also highlighted that the observed decline in residual value can be attributed to the structure of EV subsidies: in France, subsidies are not directly tied to the duration of use, which in most cases makes the purchase of a new EV more financially appealing than buying a used one.

The European Commission has announced it will come forward with a legislative proposal to accelerate the electrification of corporate fleets. According to T&E, an EU electrification target for large company car fleets would guarantee a market demand for European car manufacturers of more than 2.1 million EVs in 2030. This would deliver on average half of the EVs the manufacturers need to sell to meet their 2030 CO₂ emission standards and avoid paying penalties. Member States could also revisit their BEV subsidy policies so that support is spread more evenly over the vehicle’s lifetime.

Reference

(1) The TCO corresponds to all costs that accrue from initial purchase to re–sale, including depreciation, fuel costs, taxes, insurance, and repair and maintenance. It can also include all forms of subsidies or tax reliefs that the vehicle buyer benefits from.