Ambition is the Key Missing Ingredient in the World Bank’s Paris Alignment Approach

After years of waiting, the World Bank finally approved and released its alignment approach with the mitigation and adaptation goals of the Paris Agreement. Presented by the World Bank as “the most comprehensive institutional undertaking ever done by the Bank Group to reconcile development and climate”, this alignment approach is an important step towards the reform of the World Bank currently under discussion. But this approach won’t be sufficient, argue Alice Pauthier and Sarah Bendahou in this blog post. It could be more ambitious.

What is an alignment approach? It is a process through which an organisation, let’s say the World Bank, aims to contribute, across all its activities, to countries’ decarbonised and resilient development. It includes (i) an alignment commitment, which sets the level of ambition of the institution with specific objectives and targets, and a strategy to achieve them, and (ii) a set of assessment methodologies, tools and processes that will enable operational teams to screen and prioritize activities.

The World Bank’s Paris alignement approach sets minimum ambition

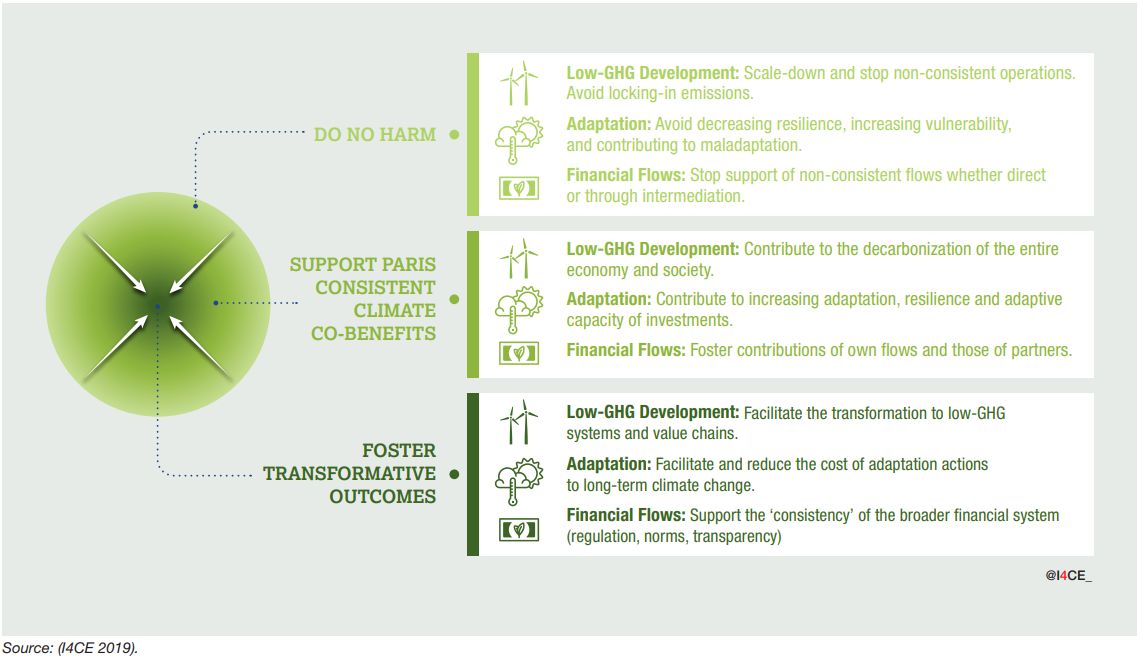

Let’s start with the alignment commitment of the World Bank. Is it ambitious? Surprisingly not more than other financial institutions, including from the private sector, who commit to “do no harm” across all their activities, or to “support climate co-benefits” in specific sectors relevant to their operations. In practice, these institutions would for example stop investing in new coal assets, accelerate investment in assets with robust transition plans, or in renewables.

It’s a good start. But financial actors can go further, and public development banks such as the World Bank are expected to go further. They should go beyond “doing no harm” or “supporting climate co-benefits”, and instead aim to “foster transformative outcomes” (see Figure 2). In other words, they are expected to not only follow what is happening in economic sectors, but to “pave the way” for the transition in developing economies and emerging markets. The World Bank can create the conditions for renewable projects to be bankable in a specific market and attract private investors. It can also contribute to accelerating the retirement of coal assets. By doing so, it contributes to changing some fundamental characteristics of the real economy.

This lack of ambition is all the more surprising since the World Bank adopted an ambitious Climate Change Action Plan last year. Additional commitments included the prioritization of key systems‘ transition (e.g. transport, cities, manufacturing, etc.) in developing countries. Yet, the World Bank’s current alignment approach does not go that far and would fail to support these efforts.

The Paris Alignment ‘Bulls eye’: actively supporting national and international transformations across all activities

Improving alignement for more impact

What about the World Bank’s instruments and processes to implement this commitment? As they stand, they will not help prioritize activities, identify how to foster transformative outcomes, and maximize the World Bank’s impact.

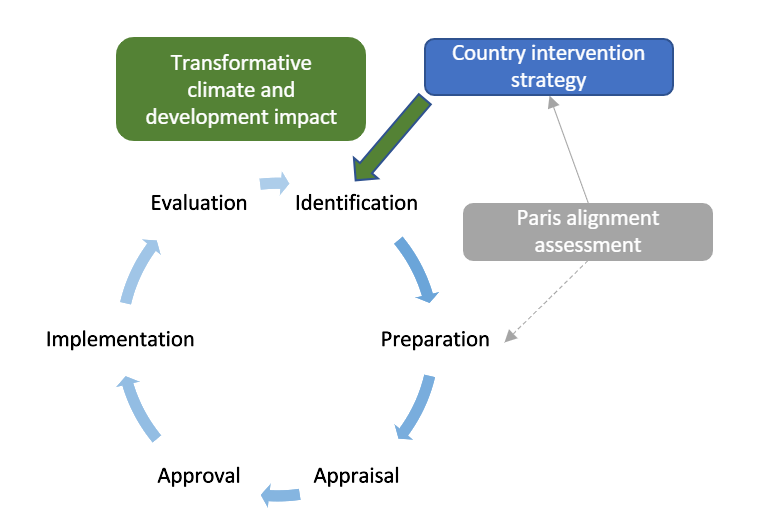

The World Bank, like other multilateral development banks, currently assesses the compatibility of projects with a country’s climate and development pathway during project preparation, as illustrated below. This timing leaves little room for significant amendments in project design, to align with country priorities and maximize impact. This alignment assessment should occur before project preparation, and even before project identification, directly informing the World Bank’s intervention strategy in the country.

The alignment assessment could even support country dialogue and ensure activities jointly identified with the country result in the most transformative climate and development outcome for local communities. This outcome would require technical and financial support for which the World Bank has identified that it has most added value compared to domestic public and private financial resources or international finance from other institutions. Such identification would be rather straight forward when countries have already developed sufficiently granular Paris-aligned long-term strategies, in which they determine the key priority climate actions by sector e.g. the development of a Y% electric mobility offer in the public transport sector by year X. It would be even easier to perform if countries define related investment priorities and financing plans that identify domestic financial resources, as well as financing gaps that require investment-enabling policy reforms and international financial support. In its alignment approach, the World Bank recognizes the importance of these country strategies and has already dedicated support for capacity building in this area that should be scaled up.

Similarly, the wider World Bank Group has developed instruments and processes to assess the compatibility of operations intermediated by a partner financial institution, such as a national development bank in a certain country. But that will not be enough to play an active role and maximize its impact. To contribute to the alignment of financial systems, the World Bank Group is expected to actively support changes in financial sector practice, and it is equipped to go further, by building the capacity of financial institutions in developing countries, and helping accelerate their own alignment journey. Along with the International Monetary Fund and other multilateral development banks, the World Bank Group is also in a position to build the capacity of national authorities to foster the integration of climate considerations in national regulation and supervision. The development of these capacity building activities should be an integral part of the World Bank’s Paris alignment approach.

At the end of the day, the World Bank’s Paris Alignment approach won’t be enough to achieve the Paris Agreement goals. It lacks ambition and will not enable the World Bank to prioritize operations with the most transformative outcomes. Maximizing impact should be high on the agenda of the World Bank reform and at the core of its future business model. This should be acknowledged by its shareholders who should provide the World Bank with the resources and mandate it needs to scale it up.