Anticipating the impacts of a 4°C warming: what is the cost of adaptation in France?

Assessing the economic implications of climate policies is essential for steering public action. Significant progress has been achieved in assessing the costs of mitigation, particularly with the publication in 2023 of the report on the economic implications of climate action. However, as the Cour des Comptes noted in its 2024 annual public report, numerous issues surrounding adaptation continue to emerge. Our recent work has nevertheless enabled us to draw five initial conclusions on the subject:

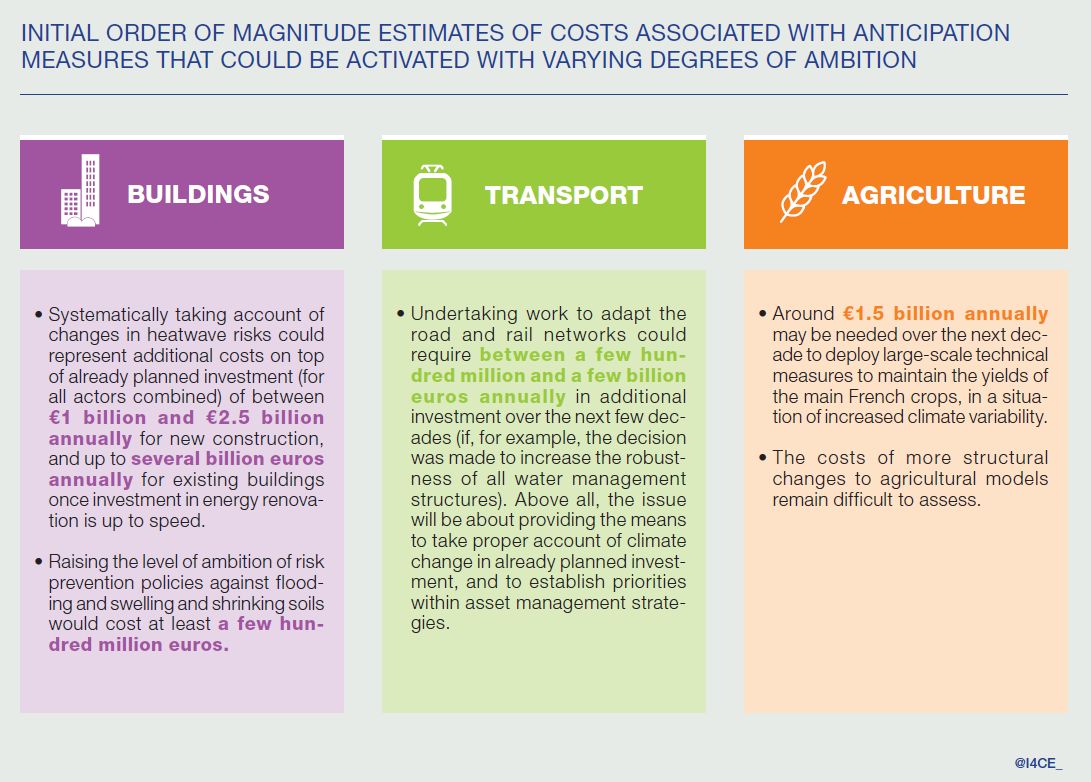

1 – Initial estimates but no single adaptation cost in France. We have been able to calculate some initial estimates for three major sectors: buildings, land transport infrastructure and agricultural crop production. These are presented in detail in the thematic sections of this document. This patchwork of different elements, of varying degrees of maturity depending on the area of activity, allows us to see the orders of magnitude of the sums involved for all economic actors. We should not, however, be too quick to calculate a single cost for adaptation in France. Such estimations are difficult because they depend both on the warming level that we wish to consider (and there is much work to be done to quantify the extent of vulnerability for each warming level) and on the way in which we collectively choose to prepare (with many of these choices still to be taken, as strategic visions of adaptation are yet to be defined). For example, flood prevention measures for a road may require works totalling several million euros, whereas organizing temporary traffic closures during flooding episodes would mean accepting a lower level of service but would also be less expensive.

2 – Without a more ambitious adaptation policy, unplanned reactive measures often turn out to be the costliest for public finances, already accounting for several billion euros a year. This expenditure includes the public cost of damage, the cost of repairing essential infrastructure and the cost of subsidies to overcome crisis. While in the short term a react and repair approach may sometimes seem simpler and cheaper than one based on anticipation, it is important to bear in mind that without structural adaptation, these costs will continue to rise and will cease to be exceptional. In addition to direct costs, there are wider socio-economic consequences (impacts on the healthcare system, labour productivity, the efficiency of transport networks, the trade balance, etc.) which will have an impact on the whole economy and reinforce territorial and social inequalities.

3 – Anticipation options are well understood and could be better deployed. These include, for example, promoting adaptated construction methods and appropriate architectural choices to maximize summer thermal comfort in buildings, even without air conditioning; reinforcing certain structures or organizing maintenance differently to improve the robustness and resilience of infrastructure; adjusting certain cultivation practices or generalizing agroecological measures to limit the effect of climate variability on agricultural production. These options can sometimes be implemented at a limited cost – particularly by incorporating adaptation into the specifications for already planned investment. Sometimes, however, they represent additional costs, or even require the mobilization of additional dedicated resources. We are just beginning to appreciate the magnitude of the costs associated with the various levers of anticipation that could be activated with varying degrees of ambition. However, the costs of more transformational forms of adaptation are difficult to identify.

4 – Among the anticipation options, a number produce sufficient economic co-benefits to be intrinsically profitable, but this is not the case for all. This observation calls for a debate on the internalization of climate risks in economic models and the distribution of adaptation costs. The scale of the socio-economic impacts often justifies proactive public intervention, which can take several forms: the direct payment of some adaptation costs by public budgets being only one possible option among others.

5 – In all cases, to ensure the best possible efficiency and distribution of expenditure, adaptation must be integrated into existing planning processes. The challenge is to ensure that the right warming level, at the right time in decision-making and investment cycles, is always taken into account, so that we can avoid being subjected to future climate change impacts as well as overinvesting in very costly adaptation measures that are ultimately never likely to be economically justified. This requires a sequenced implementation of adaptation that considers the lifespan of investments and the reversibility of decisions, as well as a visible and stable distribution of responsibilities, to ensure that the incentives for taking action are clear to the various economic actors.