Six years of carbon certification in France: an assessment of the Label Bas-Carbone

Established in 2018 and held by the French Ministry for Ecological Transition, the Label Bas-Carbone (LBC) is a financing tool for “climate positive” projects, serving the French National Low-Carbon Strategy (SNBC). Based on a carbon impact measurement combined with the assessment of various quality criteria (additionality, environmental impact, etc.), it demonstrates and certifies the climate impact of activities in France, mainly in the agricultural and forestry sectors, with the aim of enabling their financing. The LBC mainly channels private funding from companies, often in the form of carbon offsetting or carbon contributions, which is an advantage given the constraints on public spending.

Six years after its inception, this study aims to review this mechanism and its projects: what activities are being implemented in the field, what impact are they having on the climate, with what robustness or, on the contrary, what limitations in terms of measurement, environmental integrity, accessibility, etc.? This exercise is also intended to feed into the process of continuous improvement of the scheme and to provide feedback for the current implementation of the European carbon certification framework (Carbon removals and carbon farming: CRCF).

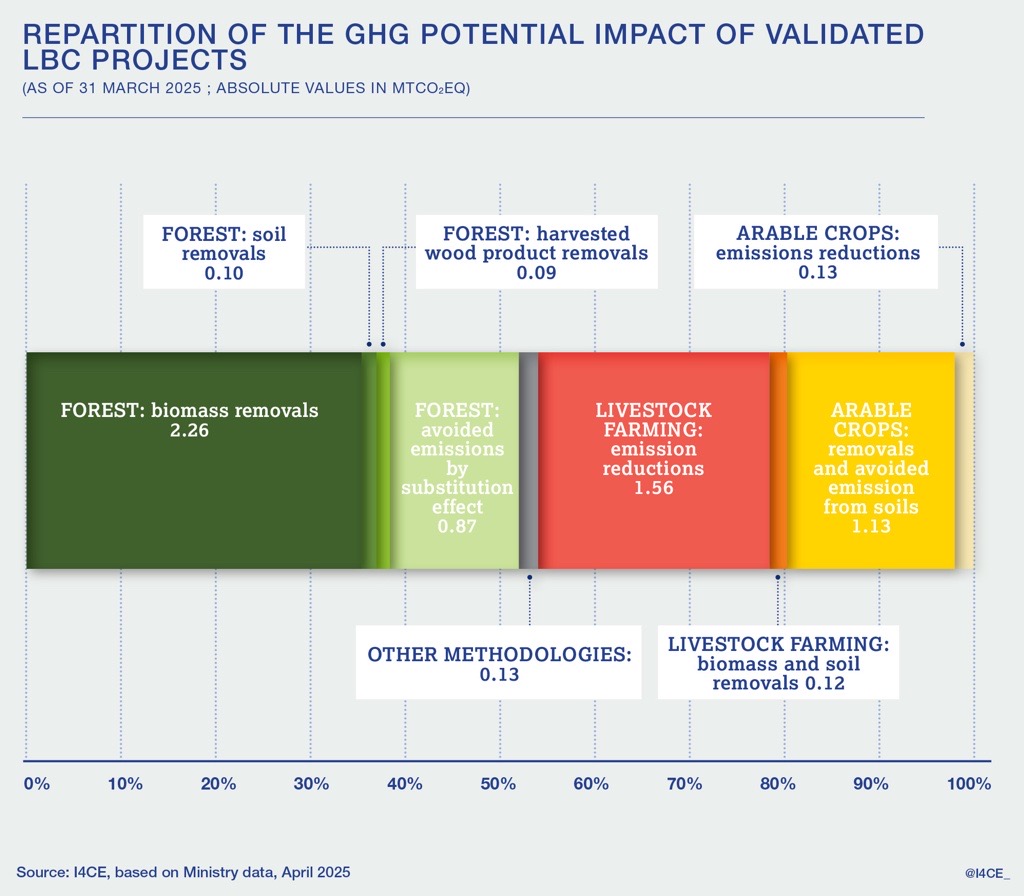

A potential impact of more than 6 MtCO2, mostly from the agricultural and forestry sectors

As of 31 March 2025, 1,685 LBC projects had been validated, representing a potential impact of 6.41 MtCO2eq, which will be verified and adjusted 5 years after the launch of each project. Four out of a total of 15 methodologies dominate: afforestation and restoration of degraded forests for the forestry sector, and low-carbon practices in livestock farming and arable-crops for the agricultural sector. The growth in LBC supply is following an exponential trend: around 2.8 MtCO2eq of potential certificates were validated in 2024, doubling the figure for 2023. The projects cover the whole of mainland France, with a planned extension to the overseas territories.

Unlike international carbon certification standards, the forestry LBC focuses on small individual projects (10.8 ha on average), whereas in agriculture, projects tend to be collective, on a larger-scale and mainly targeting large farms.

The agricultural and forestry sectors have been very active in developing projects, using the LBC as a lever to enhance their knowledge of climate issues. The LBC has also encouraged the emergence of new businesses that have built their economic model around this scheme. This dynamic, with its successes and limitations, provides valuable feedback for emerging initiatives on payment for ecosystem services or biodiversity credits.

Forests: reforestation of degraded forests first and foremost

The 1,200 forestry projects studied cover more than 12,000 ha and will generate a potential 3.3 MtCO2, including mainly:

- 3,800 ha of afforestation for a potential 1.26 MtCO2, 83% of it on former agricultural land.

- 5,000 ha of forest restoration following a fire for a potential 1.02 MtCO2, 93% of which is in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, primarily due to the fires that occurred in the summer of 2022.

- 3,300 ha of forest restoration following forest dieback for a potential 0.71 MtCO2, at least 72% of which is the result of the bark beetle epidemic affecting spruce trees in north-eastern France.

Overall, Low-Carbon Label plantations diversify the species planted, which is important for the resilience of the projects: around 5 species on average for afforestation and post-dieback restoration projects and 2.5 species for post-fire restoration projects. Apart from constrained soil and climate contexts such as the Landes de Gascogne, which restrict the possibilities, a minority of projects fail to take advantage of this diversification. The minimum mix thresholds imposed from April 2025 are therefore a step in the right direction.

Thanks to the continuous improvement process, carbon quantification is becoming increasingly well controlled. To avoid calculation errors observed in some projects, more and more parameters are set by the methodologies (growth and yield tables, rotation length), which also facilitates the work of the project developers and validators.

Substitution effects (i.e. indirect emission reduction due to the use of timber produced under the project) account for 26% of potential forestry certificates, and sometimes much more for certain projects. This particularity of the LBC among carbon standards can only be assumed if the quantification of substitution effects is realistic, with a projected decrease over time as the economy decarbonises. This is the path taken by the new version of the forestry methodologies. Greater transparency on the nature of the various carbon certificates would also strengthen the credibility of the LBC.

Between 10% and 39% of potential certificates are not generated (22% on average) due to various discounts applied to account for climate risks, possible windfall effects or bias. Further strengthening the robustness of the LBC would involve assessing these discounts as the risks increase.

Agriculture: collective, multi-lever projects in livestock and arable crop farming

The 3,500 farms involved in a Carbon’Agri or Arable Crops project are using an average of 4 levers (for example, optimising the age at first calving or introducing legumes into rotations), covering the main emission sources: enteric fermentation, fertilisation and soil carbon.

The average impact is around 1 tCO2/ha/year, mainly achieved through emission reductions in livestock farming and sequestering carbon in arable soils. However, it should be noted that what is referred to as sequestration in the soil also corresponds to mitigating soil carbon loss (avoided emissions), even if this distinction is difficult to make because of the uncertainties involved.

There are ongoing debates about carbon quantification in the two agricultural methodologies, which could be improved in two ways:

- A change to the carbon metric for the Carbon’Agri methodology (livestock farming), as the current metric encourages system optimisation, but hinders the structural changes that are essential to meet the agricultural sector’s climate objectives.

- Improvements to the methodology for arable crops, achieved through a stricter selection of eligible carbon levers and the correction of windfall effects linked to the use of modelling.

Finally, while all arable crop projects must, of course, have a positive net climate benefit, an increase in gross emissions could be permitted if offset by greater carbon sequestration in the same project. To account for the uncertainties associated with carbon sequestration in soils, a limit could be introduced to the amount by which emissions can increase.

Voluntary and compliance demand for a relatively high carbon price

Historically, projects have been financed by French companies of various sizes and from a range of sectors, as part of a voluntary carbon contribution scheme. These financiers pay an average of €35/tCO2, which is over 4 times the international market price. Despite the downturn in the global voluntary market, partly linked to a crisis of confidence, the LBC remains attractive because of its credibility and the possibility of financing very local projects.

At the same time, compliance demand has emerged since 2022 due to the French Climate and Resilience Law which requires airlines to offset the climate impact of domestic flights. This demand accounts for 40%-80% of project pre-financing at an average price of €30.7/tCO2, thereby structuring the market. This approach also encourages the most effective projects in terms of biodiversity, even if the bonus mechanism could be reviewed to avoid converting biodiversity into carbon and preserve LBC’s role as a “carbon thermometer”.

Although a minimum of 30% of projects are already pre-financed, demand, particularly from voluntary sources, remains fragile for LBC projects, particularly agricultural projects. These projects have a higher price per tonne of CO2 and a less attractive narrative than forestry projects. They also struggle to mobilise the downstream part of their value chain.

To strengthen and sustain this voluntary demand, we recommend enhancing transparency by better clarifying the different types of certificates validated within the registry, but also the need to specify the demands of funders, particularly those from downstream in the agricultural value chain.

Finally, given the fragility of voluntary demand and the constraints on public finances, it is also crucial to strengthen the compliance lever in order to unlock the necessary funding for the transition in the agricultural and forestry sectors. This could be achieved by:

- With current obligated parties, via an increase in the reference price of €40/tCO2, which would also support improvements in project environmental integrity; or via an upward revision of the share of the volume of emissions to be offset in Europe (currently 50%).

- By extending this obligation to new sectors.

The LBC: a tool for measuring carbon impact, well established across the whole of France

The LBC has established itself as an effective tool for directing private climate funding towards the agricultural and forestry sectors in France. Its open governance and bottom-up approach have been widely praised, as has its ability to engage a diverse ecosystem of stakeholders around climate issues. It has also produced benchmark tools for calculating the carbon impact of practices, which are now used far beyond the LBC. In a context where it has become essential to assess the effectiveness of the funding provided, these tools for exploring climate impact measurement are key.

The LBC is also experimenting with different ways of striking the right balance between the cost and accuracy of carbon measurement (using discount or framing methodologies, for example), with a view to ensuring both scientific rigour and accessibility for stakeholders of all sizes. This search for balance makes the LBC more accessible to project developers than most international labels. The LBC is therefore particularly well suited to small-scale projects, especially in the forestry sector.

Lastly, the LBC is also a ‘pathfinding’ tool, providing data on the implementation of “carbon” practices, technical feasibility, costs, obstacles and facilitators. This data is invaluable for supporting the development of scalable climate public policies.

A process of continuous improvement to be pursued on several points

In addition to its strengths, the LBC also has limitations, some of which have already been addressed through continuous improvement. It is therefore necessary to ensure the technical development of the label and its methodologies in line with the latest scientific advances, feedback from the field and changes in the market. Several methodological limitations have already been identified and are being or have been discussed as part of the review of the methodologies. This process is crucial, as it enables us to correct the loopholes observed and to continue to adapt to a changing context, while reinforcing environmental integrity wherever necessary. It is also to be expected that the process will increase the cost per tonne of CO2, and measures might have to be taken to ensure demand continues to be met.

Consolidating governance and transparency

The LBC is managed by the French Ministry for Ecological Transition, but governance is fairly open and bottom-up. Methodologies are proposed by stakeholders and different stakeholders participate in the Scientific and Technical Group (GST), which reviews technical developments. While this governance model has strengthened over time, there is still room for improvement: greater harmonisation of project validation processes by regional authorities, greater transparency around GST reports, the creation of a consultative ‘users platform’ and securing dedicated funding to ensure regular revision of methodologies. Finally, while some data can already be consulted for each project on the Ministry website (e.g. co-benefits, species and levers), more data should be made public to improve transparency (e.g. project discounts and carbon calculations).

New prospects and new challenges

Finally, alongside internal technical and governance improvements, the LBC will be confronted with new challenges in the coming years, in line with the national and international context. Firstly, mandatory independent third-party audits, 5 years after project validation, should enable potential GHG impacts to be transformed and adjusted into verified impacts. Secondly, efforts to diversify the practices targeted by the methodologies should continue in order to better reflect the range of possible climate actions.

The LBC needs recognition beyond French borders, particularly to ensure its attractiveness to major groups, based in France. This could involve providing documentation in English or seeking accreditation by the meta-standards (ICROA, ICVCM) that label the quality of certification standards. Finally, the arrival of a carbon certification framework at European level (CRCF) represents both an opportunity and a challenge for LBC. There are two possible scenarios for the coming years: either LBC will be integrated into the CRCF, leading to significant changes such as abandonment of ex-ante credits and indirect emission reductions or the transition to temporary certificates; or the LBC will remain independent, which could result in a loss of attractiveness for companies operating on an international scale.

Supported by