Climate finance at COP30: Progress, pitfalls, persistent challenges and the path ahead

A few weeks ago, COP30 concluded in Belém with all parties agreeing on a “global mobilization” (or mutirão) against climate change, proving that multilateralism remains a viable path to enable action, despite strong geopolitical and economic headwinds. However, Belém delivered underwhelming results: no roadmap to transition away from fossil fuels –despite a powerful push from over 80 countries, a lack of concrete decisions on deforestation –disappointing for an “Amazon COP”, and mixed results on the global goal on adaptation, among other outcomes.

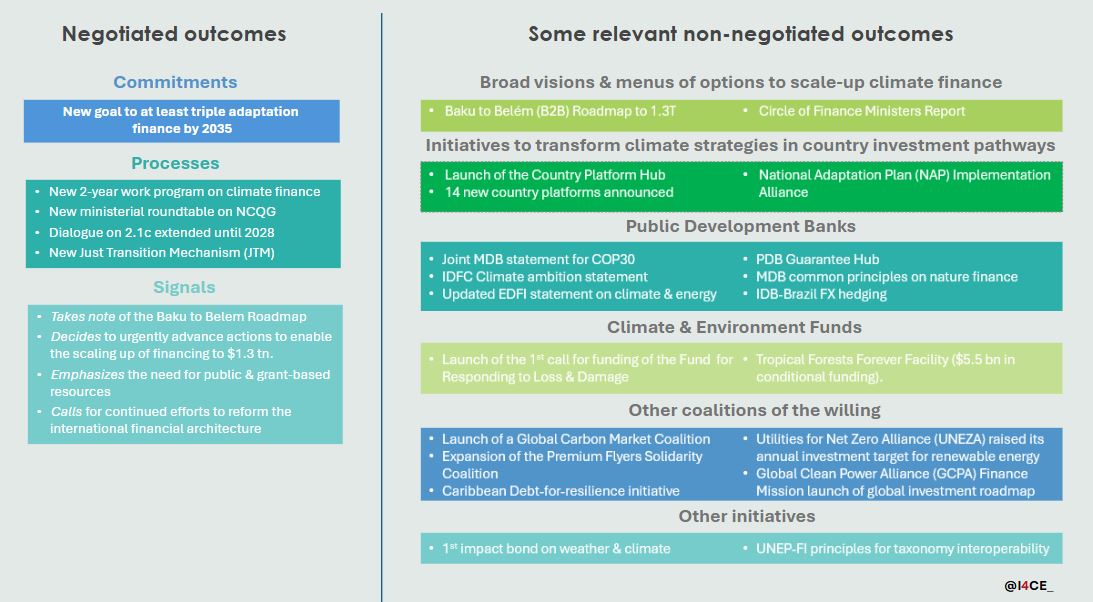

On climate finance, COP 30 outcomes reflect a contrasted picture that shows that the implementation path may lie outside the negotiation rooms. On the one hand, official negotiations failed to shift from ambition to implementation. Despite having agreed on a New Collective Quantified Goal on climate finance (NCQG) last year and commendable efforts through innovative formats proposed by the Brazilian presidency, discussions quickly drifted back to an entrenched battle on yet another headline quantitative target –this time on adaptation. On the other hand, Belém registered interesting progress on many non-negotiated outcomes: from broad visions and menus of solutions to methods and metrics, from public development banks (PDBs) to vertical climate funds and coalitions of the willing (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: COP30’s main negotiated and non-negotiated outcomes on climate finance

This blogpost highlights the progress achieved in COP30’s negotiated and non-negotiated outcomes on climate finance, as well as areas for further progress ahead of COP31.

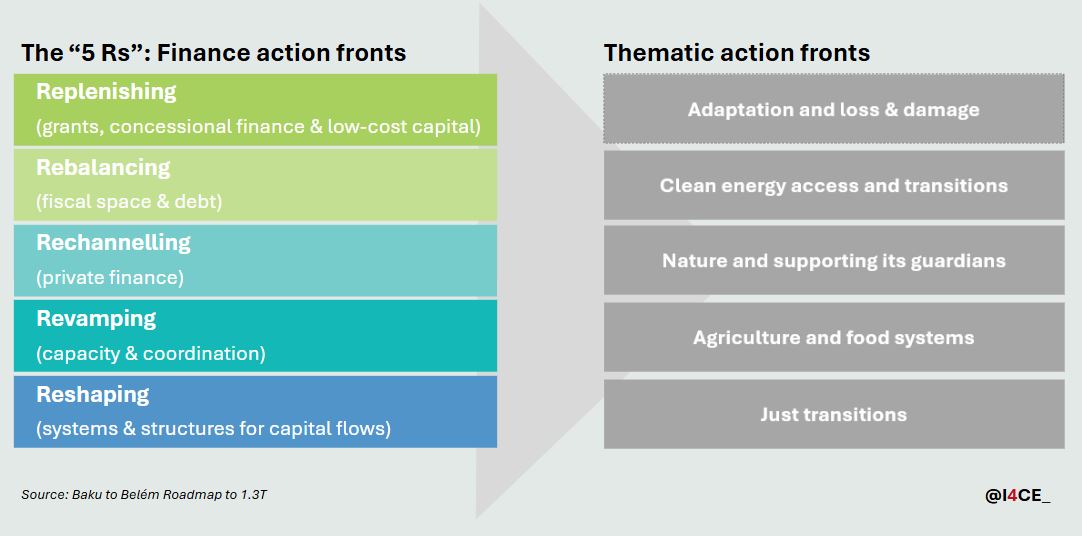

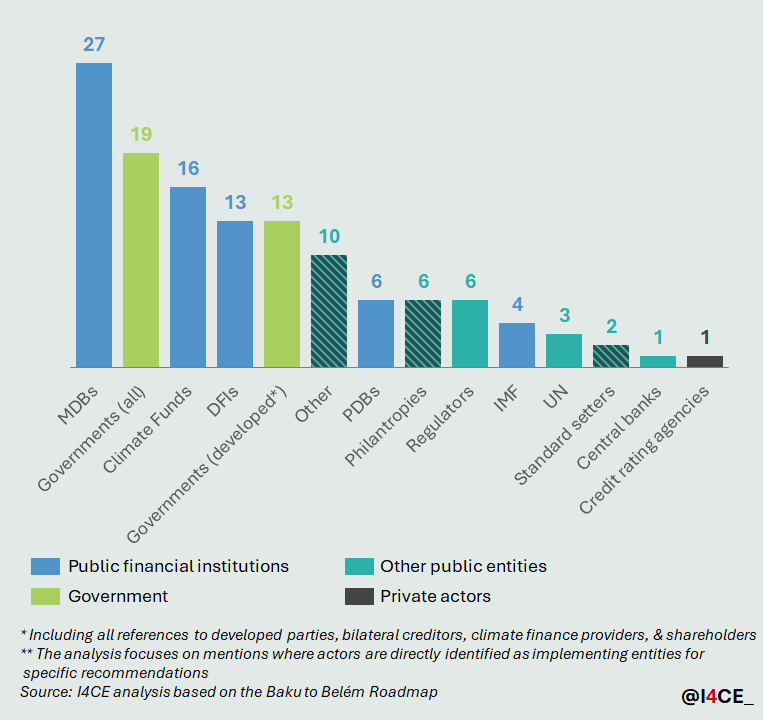

Progress: a global menu of solutions to scale up climate finance, and dynamic coalitions to implement them

Belém’s first positive legacy on climate finance is the “Baku to Belém (B2B) Roadmap to 1.3T” and the report of the COP30 Circle of Finance Ministers (CoFM). Together, these important documents provide a comprehensive menu of solutions, with dozens of concrete measures and recommendations addressing a wide spectrum of issues related to scaling-up climate finance, dealing with all kinds of flows – public and private, domestic and international – and actors, from MDBs and vertical climate funds to credit rating agencies and regulators (Fig. 2 and 3).

The Circle of Finance Ministers (CoFM), in itself, is another great outcome of Belém. This sui generis and rather heterogeneous group of 35 finance ministries bridges traditional silos – between climate and finance – and help build collective ambition. In an increasingly fragmented world, the remarkable feat of having a group of countries representing 60% of the world population and GHG emissions(1) signing off on a common declaration welcoming the CoFM report and committing to work together “to advance practical solutions that accelerate the flow of climate finance” is worth highlighting.

Figure 2: Breakdown of the B2B roadmap recommendations, by finance and thematic action fronts

COP30 also built momentum around national financing plans or initiatives aiming to transform climate strategies in country investment pathways –in line with recommendations from the B2B roadmap and the publication of the third generation of NDCs. In partnership with the Green Climate Fund (GCF), 13 countries and one regional coalition announced plans to establish new “country platforms” under the GCF Readiness Programme(2) and a regional platform of African Island States Climate Commission member countries. These platforms are framed as mechanisms to move from fragmented projects to coherent investment architectures, which in its framing aligns with I4CE’s view on the central role of financing plans for the transition and ongoing work on tools to support countries in designing and implementing them.

In addition, the Country Platform Hub (CP Hub) was launched as part of COP30’s Solutions Acceleration Plan to connect and support national efforts to design and operationalise country platforms. The CP Hub aims to serve as a coordination mechanism linking countries to technical assistance, knowledge and finance, ensuring that global support systems respond effectively to country needs. The Hub builds on partnerships among key global initiatives(3), and anchors coordination in ministerial networks such as the COP30 CoFM, the Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action and the CVF–V20. It will be guided by a Steering Committee with a majority of developing-country representatives and supported during its incubation by a light Secretariat hosted at the Africa Climate Foundation, with seed funding of almost USD 4 million to finance early activities on governance, coordination and knowledge systems, as well as a “Spark Plug” window to back early-stage platform design. This is welcome towards a coordinated mobilisation of financing options, which, as a 2024 I4CE publication shows, remains a major roadblock towards efficient financing plans.

Adaptation and resilience were also pulled more firmly into the financing plans discussion. Alongside a political signal to triple adaptation finance by 2035, COP30 saw the launch of the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) Implementation Alliance, a multi-stakeholder partnership led by the COP30 Presidency, UNDP, the governments of Italy and Germany, the NAP Global Network and the NDC Partnership. The Alliance, established as a Plan to Accelerate Solutions under the COP30 Action Agenda, aims to accelerate collaboration among organisations supporting NAP implementation, mobilize public and private investment for national adaptation priorities, and help countries turn adaptation planning into investment strategies and bankable project pipelines.

Public development banks also rose to the occasion in Belém. Despite pressure from some shareholders, MDBs showed progress in delivering climate finance – with a record US$85 billion to low- and middle-income economies in 2024, a 14% increase from previous year and reaffirmed their climate commitments through a new “joint MDB Statement for COP30”. The International Development Finance Club (IDFC) – a coalition of 27 development banks which provided $1.9 trillion in green finance and represented over 40% of global public climate finance between 2019–2023 – also issued a new climate ambition statement, confirming its commitment to finance the “progressive transition away from fossil fuels” and expanding its action to new issues –from Article 6 to country platforms and nature finance. European development finance institutions also pledged to increase the share of climate finance in their portfolio, from 30% today to 40% in 2030. PDBs and other financial actors pushed the concept of “transformational finance”, moving beyond climate mainstreaming and co-benefits to unlock systemic impact, with the publication of a common position endorsed by a group of public and private financial institutions totaling US$4 trillion in combined assets(4).

The role of PDBs is increasingly recognised, confirming their central place in the climate finance architecture. From MDBs to DFIs and national development banks, they feature among the most often cited implementation entities in the B2B roadmap (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Implementing entities identified in the B2B roadmap

Finally, Belém also showed that coalitions of the willing could deliver progress when consensus-based negotiation fails. On fossil fuels, there was a coordinated effort by more than 80 countries to include a roadmap on transitioning away in the COP decision. While not included in the last version of the “Global mutirão”, this led the Netherlands and Colombia to announce the organization of a First International Conference for the Phase-Out of Fossil Fuels in April 2026. Coalitions of the willing were also active on the finance front, as evidenced by the momentum created around the Global Solidarity Levies taskforce, with the expansion of its Premium Solidarity Flyers Coalition. If well-structured and transparently linked to measurable outcomes, solidarity levies could play a catalytic role in bridging the climate-development finance gap. They would complement, not replace, official development assistance (ODA), providing predictable, debt-free resources for countries most vulnerable to climate and economic shocks.

Possible pitfalls: positive dynamics that need to be converted and worrying trends that need to be averted

Belém moved the needle forward on several other finance-related issues: whether this can be counted as actual progress will depend on the dynamics in the coming months. The evolution of the role and status of both the B2B Roadmap and the Circle of Finance Ministers will be key parameters to watch as we move into 2026. The Global Mutirão decision provides several signals to maintain the momentum around the B2B Roadmap and CoFM process. First, it “decides” – the strongest possible verb in UNFCCC negotiations – “to urgently advance actions to enable the scaling up of financing” for developing countries and puts a welcome emphasis on the critical role of grant-based and highly concessional resources to fund adaptation and resilience in Least Developed Countries and Small Island Developing States.

COP30 launched new processes which could use the B2B roadmap and CoFM report as starting points to advance implementation. It established a two-year work programme on climate finance – with a focus on Article 9.1 –which could become a useful platform to discuss and advance the implementation of the US$300 billion goal. In parallel, Belém decided to convene a ministerial roundtable on the implementation of the NCQG as a whole, an interesting format if it is to be connected to the outcomes of the B2B and CoFM processes.

Moving ahead with the B2B Roadmap and CoFM report will also require fine-tuning their content, prioritizing the most impactful and feasible measures and building coalitions to implement them. While the essence of the B2B roadmap was to cover all flows and actors, it still focuses heavily on concessional finance provided by traditional donors –directly or through multilateral channels. A detailed analysis of implementing entities identified within the 75 recommendations of the roadmap shows that private actors are largely exempted from any action, although the importance of private finance mobilization is recognized in the roadmap. The role of emerging climate finance providers such as China or Gulf countries is equally absent –even if experts agree that “South-South” cooperation will have to play a role to get to US$1.3 trillion.

Finally, while showing no sign of decreased ambition on climate, MDBs remain under the pressure of the current US administration as their main shareholder. The World Bank, whose climate strategy could be updated in 2026, is a case in point – with the US Treasury having already expressed opposition to its current 45% climate finance target and doubts about its fossil fuel exclusion policy. The volume of green finance provided by large national development banks also decreased for the second year in a row – from US$199 to US$174 billion, and from 19% to 13% of total new commitments. While this is mainly due to changes by few large institutions –such as the China Development Bank– and exogenous factors –exchange rate fluctuations and a contractionary macroeconomic environment, this remains a worrying trend to watch in 2026, especially as budget cuts on ODA will put additional constraints on European development banks, which currently provide the lion’s share of bilateral climate finance to developing countries.

Persistent challenges: official negotiations are (still) mainly focused on headline targets

Far from moving “from headline trillions back to effective millions” – that is, focusing on country-led implementation – negotiations in Belém quickly drifted back to an entrenched battle on yet another high-level target.

COP30 did generate a much-needed momentum on adaptation, with the new commitment to triple adaptation funding by 2035, yet this outcome satisfies no one. Developed countries argue it reopened the NCQG and should have been paired with higher ambition on mitigation, while developing countries lament the distant time horizon, pushing instead for a 2030 target. Overall, the materiality of the commitment is questionable given its non-binding wording, the absence of a clear baseline, and the likely failure to meet the previous commitment taken in Glasgow. COPs’ persistent focus on top-down macro-figures risks diverting efforts away from concrete implementation.

Moreover, COP30 missed the opportunity to substantively discuss – or build consensus around – all or even part of the 75 concrete measures listed in the B2B Roadmap. The cover decision merely “takes note” of the roadmap and establishes yet another set of processes.

While other tracks showed Parties’ ability to transcend usual dividing lines, negotiations on climate finance rapidly returned to familiar bloc-against-bloc rhetoric, pitting the so-called “Global North” and “Global South” against each other. On the one hand, developing countries focused on Article 9.1 – under which developed parties have an obligation to provide climate finance to developing ones – and a new US$120 billion target for adaptation by 2030. On the other hand, developed countries stressed the need to expand the donor-base, to stay within the framework of the NCQG and to match any new commitments on adaptation finance with increased ambition on mitigation efforts.

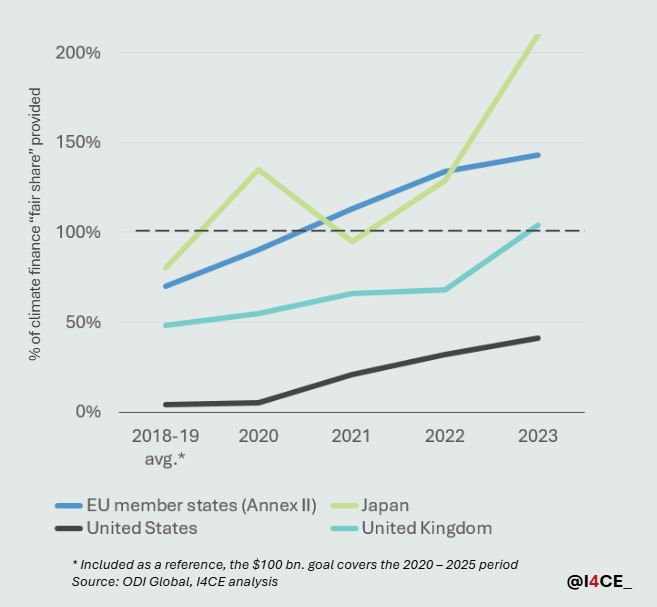

As we move towards implementation, it can be helpful to take a more granular perspective on the debates. Analyses have shown that some countries have provided more than their “fair share(5)” of the US$100 billion goal agreed in Copenhagen, while other parties are lagging (Fig. 4). The EU remains the largest provider of public and publicly mobilized climate finance, with over €40 billion in 2024 while the US keeps underproviding. So, when it comes to providing climate finance, the “Global North” is a mixed basket, rather than a homogenous group. Similarly, the “Global South” doesn’t represent a single standpoint on climate finance. Needs and priorities vary significantly across income categories and based on specific country contexts. Upholding the key UNFCCC principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities” is compatible with non-traditional donors stepping up to provide climate finance, given their mounting share of cumulative emissions and current income levels. Recent analysis shows that there is a strong case for non-traditional donors to provide 20-30 percent of any climate finance total.

Figure 4: Provision of climate finance by selected donors,

compared to their “fair share” of the $100 billion goal.

The path forward to COP31

Although the results were mixed, Belém had the right ambition for climate finance: shifting from headline targets to effective implementation. To do so ahead of COP31 in Antalya, it is essential to capitalise on the efforts of the Brazilian presidency:

- By maintaining the Circle of Finance Ministers as an active and dynamic forum to discuss and advance concrete measures to scale up climate finance to US$1,3 trillion. The Republic of Türkiye and Australia should commit to convening a COP31 Circle of Finance Ministers, building on the success and outcomes of Brazil’s own initiative.

- By strengthening the convergence between climate finance talks inside and outside UNFCCC processes. COPs have achieved undisputable results and have proven their usefulness, but they are not effective platforms to advance implementation, including climate finance issues. The COP31 President (Türkiye) and President of Negotiations (Australia) should emulate Brazil, by striving to use every international summit and milestone as a platform to discuss climate finance. France and India will respectively chair the G7 and the BRICS in 2026. Both countries have engaged in the COP30 Circle of Finance Ministers and both could help Türkiye and Australia to build consensus on some of the concrete measures proposed within the Baku to Belém roadmap. The Spring and Annual meetings of the World Bank and IMF will also be decisive milestones, especially in 2026 given the role of MDBs in the international climate finance architecture.

- Finally, by making sure the processes launched in Belém translate into concrete action. For example, the newly-established ministerial roundtable to discuss the NCQG could be linked to a future COP31 Circle of Finance Ministers, or even elevated to a Head of State or Government summit – mirroring the Colombia-Netherlands initiative on fossil fuel phase-out.

Belém reminded us that while negotiations still stumble over old divides, progress is taking shape outside the formal process. COP30 – and especially the preparatory work undertaken by the Brazilian presidency – offered a blueprint for how implementation can accelerate when coalitions of the willing, public development banks, and forward-leaning governments choose to act. The challenge now is to turn this momentum into a durable architecture that delivers predictable, scalable finance, not more headline battles. If Türkiye and Australia seize this opportunity at COP31, Belém could yet be remembered not for what it failed to agree, but for what it set in motion.

References

- Australia and Japan did not sign the ministerial declaration, though both claim this was for institutional rather than substantive reasons.

- Cambodia, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, India, Kazakhstan, Lesotho, Mongolia, Nigeria, Oman, Panama, Rwanda, South Africa and Togo

- Including the GCF, NDC Partnership, Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF) and V20 Group of Finance Ministers, Finance in Common (FiCS), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Global Capacity-Building Coalition (GCBC).

- Including the Mainstreaming Climate in Financial Institutions Initiative, for which I4CE serves as the Secretariat

- Fair shares are determined based on each donor country’s historical responsibility for cumulative greenhouse gas emissions, its gross national income and its population size.