Climate: five key debates from the French marathon budget

Climate change and ecological planning are taking centre stage in this autumn’s French budgetary measures. The public finance programming act, which has yet to be discussed with the Senate, now requires the government to set out a multi-year funding strategy for planning. The finance bill for 2024, which will go through Parliament soon, earmarks an additional €7 billion in transition support for households, businesses and local authorities. This €7 billion does not, however, resolve the issue of financing the climate transition, and in this post we provide an overview of the key climate debates that will take place in France, or ought to take place according to I4CE, during this veritable marathon budget.

Debate #1: is an extra €7 billion sufficient?

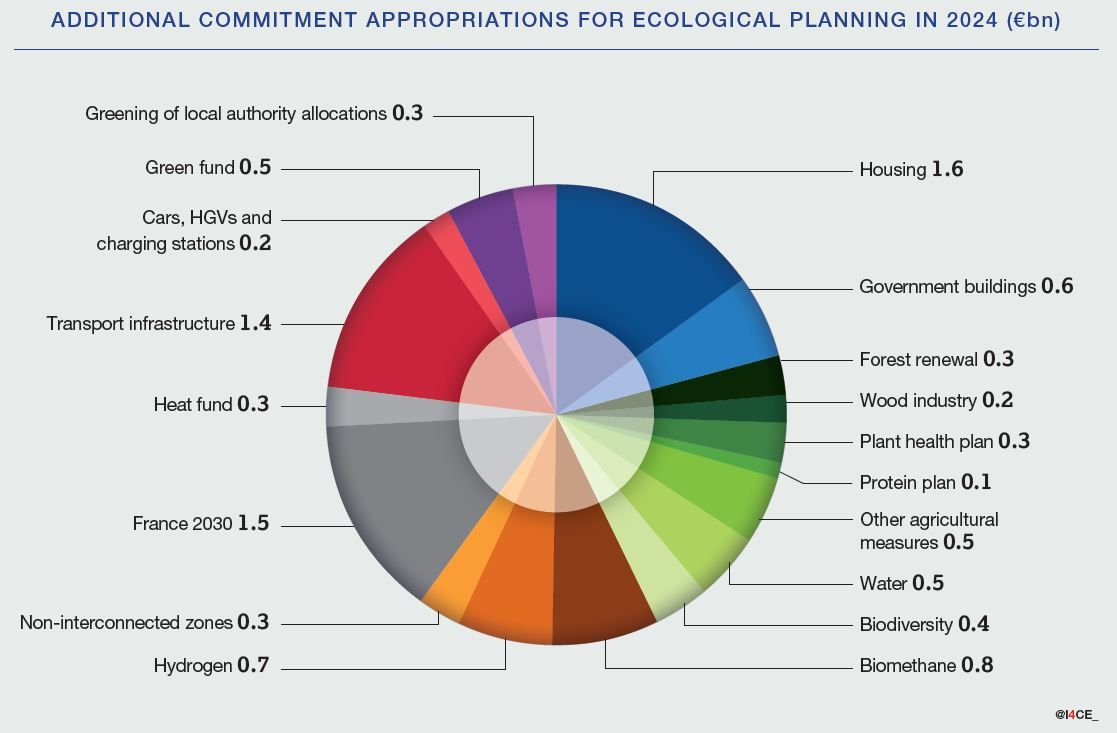

Two key figures feature in the government’s draft budget: €7 billion is the spending increase on ecological planning planned for 2024 (payment appropriations); €10 billion is the spending increase committed by the government from 2024, even if it means paying for it later (commitment appropriations). According to the French Prime Minister, this is “an unprecedented investment by the State in the ecological transition”, which should enable the renovation of more private homes and public buildings, the modernization of public transport infrastructure, and the acceleration of electric vehicle deployment and the agricultural transition. This increase is unprecedented. Only the Covid crisis and its recovery plan have triggered – momentarily – such significant funding increases for the transition in the last ten years.

Source: French governement, September 2023

Parliament will analyse the text in detail, which will give rise to proposals to amend the government’s draft budget, whether to increase certain financial packages, to reduce others, or to question the effectiveness of aid. This is good news. The government’s figures are based on interdepartmental compromises and assumptions regarding the funds that will be matched by the private sector and local authorities. It is right that it should be subject to parliamentary and public scrutiny.

For example, the additional budget of €1.4 billion earmarked by the government for transport infrastructure must be questioned, given the scale of the investment required, according to the Conseil d’Orientation des Infrastructures. As for adaptation, the public funding requirements have not yet been assessed as part of the ecological planning process, but while waiting for the future National Climate Change Adaptation Plan and the 2025 budget, a number of financial packages would enable better climate change anticipation.

As shown above, there is clearly a need to increase expenditure in certain sectors. It will certainly be necessary to spend better, to ensure that every euro paid out actually leads to emissions reductions and greater resilience in the face of climate change. This autumn’s budget will provide an opportunity to debate the reform of MaPrimeRénov’ – a government programme to encourage renovations to improve the energy efficiency of buildings – and the reform of the bonus-malus scheme to promote cleaner vehicles. A debate is also required on the need to take adaptation in public investment into account, to avoid creating infrastructure or housing that is not adapted to tomorrow’s climate, and which will therefore need further modifications in future.

Debate #2: Is it sustainable to gamble on the “green debt reduction” to balance the budget?

How can we finance the increase in transition expenditure? While Jean Pisani-Ferry and Selma Mahfouz’s report recommended using budget savings, it also advised that the levers of debt and higher taxation should not be ruled out. The government has chosen a different option: its 2024 draft budget essentially sets out plans to finance the ecological transition by making savings elsewhere in the budget, first and foremost, through the removal of the tariff shield.

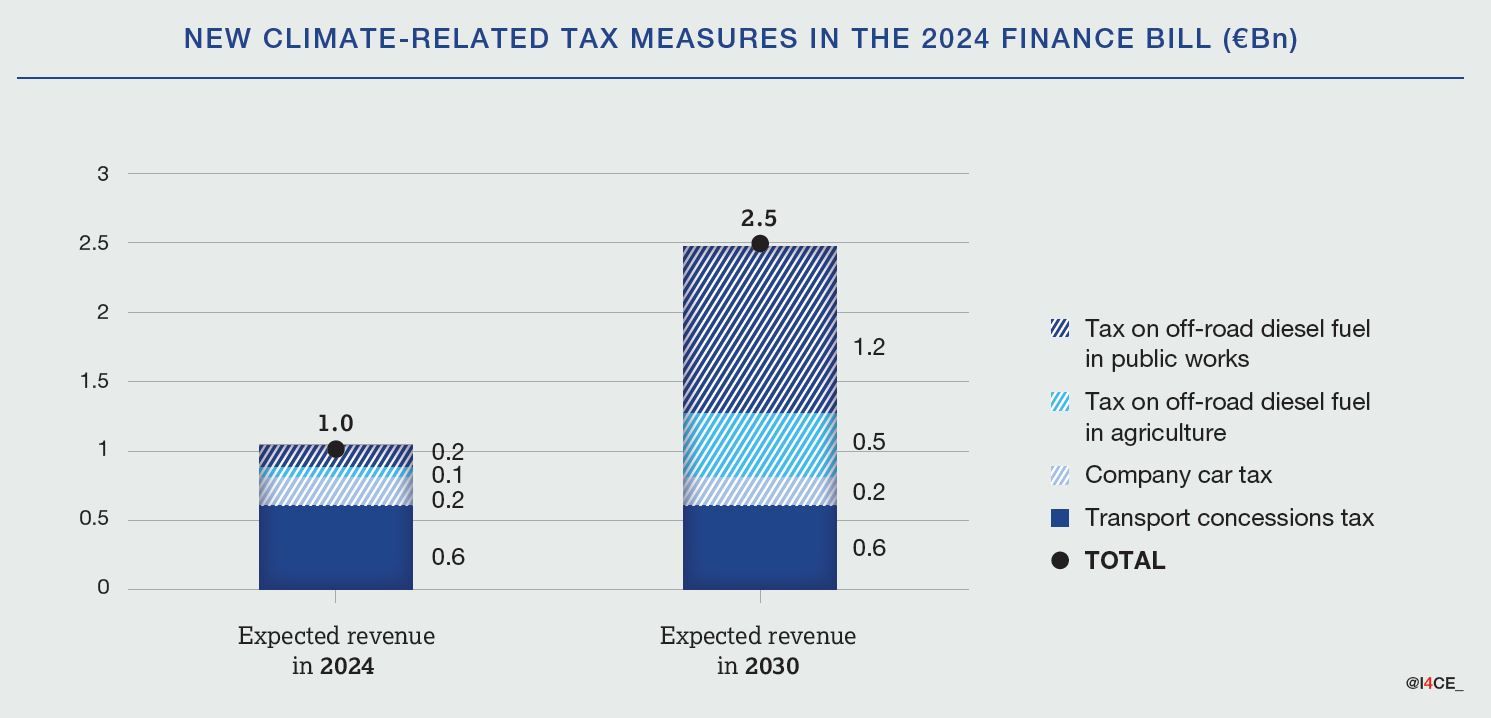

The government’s draft budget also includes a number of tax increases that can be described as environmentally friendly. The French government has made several mentions of raising the solidarity tax on airline tickets, but ultimately this has not been included in the bill submitted to Parliament. The bill does, however, provide for the reduction and elimination of certain tax concessions on non-road diesel by 2030, which currently benefit agriculture and public works companies. This measure, which also serves as an incentive, is not expected to generate any new revenue to balance the budget: the affected sectors benefit from compensatory measures which, moreover, seem to do little or nothing to encourage the transition. The increase in taxation on company cars, which should contribute to the greening of the fleet, will not support the financing of new transition expenditure, since this revenue is allocated to the social security system. New revenue to finance the transition is instead expected to come from the “tax on the large-scale operation of long-distance transport infrastructure”, which should generate around €600 million.

Source: review carried out by I4CE, the hatched areas represent revenue that should be subject to compensatory measures, or that has already been earmarked for expenditure unrelated to the climate

How will the budget be balanced after 2024? It will not be possible to generate more savings from the tariff shield, so the Ministry of Economics and Finance will rely on the ramping-up of pension reform, unemployment insurance and the end of the Pinel programme (a scheme to encourage investors to rent out their new build properties). At the same time, the need for additional public spending will increase, at an accelerating rate, as ecological planning is implemented on the ground. For example, costs are likely to triple to meet the very ambitious targets for renovating public and private buildings. The parliamentary debates will perhaps enable a little change in the balance of the next budget in terms of financing transition expenditure. These debates should at least bring the options and positions of the various political forces into sharper focus, so that a possible compromise can begin to emerge for the future.

Debate #3: Does the budget enable all households to access the transition?

The Yellow Vests protests made several things clear: the transition must be accessible to the middle class and those of lower socioeconomic status; efforts must be fairly distributed; and public policies must take the differences between households into account, whether in terms of financial capabilities or lifestyles. The State budget is an important lever for ensuring that the transition is “fair”, an issue on which the government will be judged. Who will benefit from the extra €7 billion in funding? Will there be enough support to ensure that everyone has access to the transition? Who will be the main contributors to the increase in ecological revenue?

Ostensibly, budgetary efforts will be targeted at those who will find it hardest to make the transition: low-income households will receive extra support for home renovations and for purchasing clean vehicles, social leasing schemes for electric vehicles will be supported, and everyday mobility will be prioritized to the detriment of high-speed rail links in the transport infrastructure. But these plans must first be confirmed, and subsequently debated. It will be useful to examine the way the government records these issues when it publishes the report on the environmental impact of the State’s budget, the so-called “green budget”, which is expected in the next few weeks. It must be remembered that, for the middle classes, the investment cost of home renovations and accessing electric transport represents more than a year’s income and – according to an I4CE study to be published in mid-October – the remaining costs after subsidies are often greater than any savings or debt capacity.

Debate #4: Is the financial equation sustainable for local authorities?

While the government is increasing its transition spending by €7 billion in 2024, it is also counting on the strong mobilization of other public and private actors, first and foremost the local authorities (town halls, departments, regions).

For local authorities, the first challenge of the current budget debate is to clarify the share of the budgetary effort entrusted to them as part of national ecological planning: without a shared vision of their requirements, it is difficult to have discussions about funding. Communes, inter-municipalities, departments and regions are responsible for the bulk of public investment and I4CE has estimated that to achieve carbon neutrality the investment needs of local authorities are more than €6.5 billion annually by 2030 in the building, energy and transport sectors alone. This already substantial requirement is actually a minimum, since it does not account for recent inflation, expenditure linked to adaptation, waste and biodiversity policies, or operating expenditure related to the development of transport infrastructure.

The second issue for local authorities in the 2024 finance bill concerns the changes in government funding for “climate” initiatives. The “Green Fund” package has been increased by €2.5 billion over four years, and the finance bill provides for a “greening” of other investment grants. This reflects the State’s intention to continue increasing its targeted support for local authority climate action that started with the recovery plan. The exact sums and management methods for these funds, as well as the objectives targeted, will need to be analysed in greater depth during the upcoming debates (I4CE will provide a detailed review this autumn).

Nevertheless, discussions on the financial conditions that will enable local authorities to strengthen their commitment to climate change must be viewed from a broader perspective than can be assessed by examining the State budget alone. Due to their independent management, local authorities have the revenue and expenditure margins to make their own choices, each according to their own territorial and budgetary specificities. The third issue at stake in the autumn budget discussions, at a time when ecological planning is entering its territorialization phase, is therefore to know how the acceleration of climate action by local authorities fits into the government’s vision of the medium-term development of their finances.

Debate #5: Multi-year public finance programming

While the 2024 budget, as we have explored, will certainly be a challenge, this is only a preview of the difficulties that lie ahead. The need for public spending to break through the investment barrier is set to increase until the end of the five-year period, and the State and local authorities are likely to find it more difficult to balance their budgets. Addressing this reality requires preparation, which is why members of parliament have asked the government to publish a multi-year strategy for financing the transition as early as next year – this request has met with government approval as part of the public finance programming law. This strategy will be debated each year in Parliament and updated on an ongoing basis. It does not have the same normative value as a public finance programming law designed specifically for the transition, as exists for research and the military. It is, however, very positive and represents an important step forward.

For more than two years I4CE has been urging the government to draw up a plan for the long-term financing of the transition, an idea that has attracted a growing consensus including from MEDEF, NGOs, the Cour des Comptes, members of parliament and, ultimately, the government. This consensus will no doubt evaporate when it comes to deciding on the strategy’s content and, in particular, the division of the financial effort among public and private sectors. There is likely to be a lot of posturing and preconceived ideas. Hopefully, the drafting and discussion of this strategy will enable us to move beyond such tendencies, because everyone will be required to analyse the financing details for each sector, from school renovations to industrial decarbonization. The bold hope that “the public must pay” or the more lackadaisical belief that “private finance will take care of it” can no longer be justified.